Beautifully detailed and often rich with symbolism, 17th century embroidery is a niche area of collecting, with rare surviving examples attracting competitive bidding when they come up for auction.

Embroidery is an ancient form of embellishment, the origins of which have been lost to the mists of time. However, the main influences on English embroidery in the medieval to early modern periods came from the East, brought back from Byzantium by the Crusaders in the 11th century. Rich silks, dyes and stitching techniques were adopted, as were elements of Byzantine iconography such as the Tree of Life. Initially, fine embroidery was predominantly used in an ecclesiastical context, but over the centuries techniques were refined, becoming ever more elaborate as they were absorbed into the secular world.

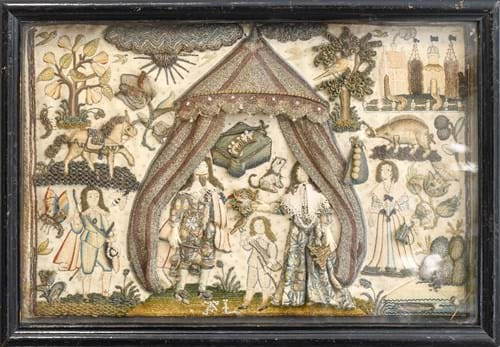

A Stumpwork Panel Depicting Charles I and Queen Henrietta Maria, mid-17th century (Sold for £4,800 plus buyer’s premium)

From the 15th century onwards, the European technique of broderie en relief began to be used in ecclesiastical robes and decorative hangings, in which light padding was added to bring elements of the embroidery into low relief. However, by the mid-17th century, this had developed into complex three-dimensional stumpwork, in which parts of the decoration were stitched separately, then stuffed and backed before being sewn onto a piece of backing fabric. For smaller decorative elements, such as leaves or insect wings, metal wire was used to create naturalistic three-dimensional structures.

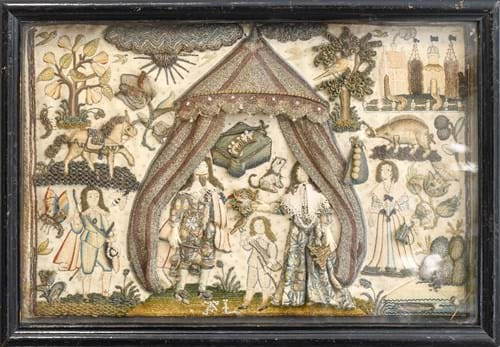

A Mid-17th Century Stumpwork Picture, with a Lady, Fruits, Flowers and Insects (estimate: £2,000-3,000 plus buyer’s premium). To be sold as part of The Selected Contents of Bell Hall, Naburn, York, a single-owner sale on 15th November 2024

Sewing was a skill all girls were taught, but in wealthier households it was developed into an art form with embroidery, and stumpwork was the pinnacle of achievement, used for highly prized decorative objects such as mirror frames and caskets as well as flat textile pictures to be displayed in protective frames. It is thought that, given the similar design of extant examples, these might have been sold as kits, with the design pre-drawn and all the materials included, much as tapestry kits are still sold today.

Stumpwork was at its height of popularity during the Civil War and Restoration, a time of shifting allegiances and turmoil. From surviving examples, we can see how stumpwork pictures were a way of displaying loyalties. In addition to biblical and mythological scenes, favourite subjects were Charles I and Henrietta Maria, and Charles II and Catherine of Braganza, who were sometimes disguised as biblical characters. The figures, often under a canopy, would be surrounded by decorative devices rich with symbolism: lions and leopards represented England, caterpillars and butterflies were associated with Charles I, and oak trees and acorns with Charles II. Other popular motifs were castles, stags, birds, fruit, flowers and insects.

A Needle and Stumpwork Mirror Frame, mid-17th century, worked with portraits of Charles I and Queen Henrietta Maria (Sold for £8,120 plus buyer's premium)

Each element was worked in silk, wool, silver and gold threads, with felt padding or even stuffed with hair. Ribbons, beads and shells could be added as extra embellishments. The resulting embroideries were full of quirky detail and charm, and when new would have been a dazzling sight. Now, sadly, even the best-preserved examples are faded and have lost their impact. However, we can still marvel at the skill of the embroiderer, and the complex range of contrasting stitches used to create texture and effect.

At auction, the most detailed stumpwork pieces in a better state of preservation can sell for tens of thousands of pounds, such is their rarity. However, there are some wonderful examples on view in museums and country houses across the UK and are well worth seeking out.